This blog exists as an outlet for my weird brain in instances where I read an article which is mostly fine, but is very slightly wrong in some way. Lately this has happened several times and the fact that someone was wrong on the internet has caused me to spend hours in a tizzy. Obviously this is not behavior that is unique to me, and many people have spent hours rage-posting on various comment sections, forums, and other cursed places of the internet. What is unique to me is that the things sending me into a tizzy have mostly been sloppy data analysis, and I have responded by spending hours doing my own data analysis and making lots of graphs. This has proven to be a surprisingly rewarding endeavor. I like making graphs, the things that I have been getting worked up about are mostly topics that I am passionate about, and in the process of furiously analyzing data, I’ve learned a bunch of stuff, some of which even contradicted assumptions that I had going into the process.

It’s been rewarding enough that I’ve decided to invest time and effort into the process in a somewhat more formal way, and I have decided to subject you, the reader, to the fruits of my weird brain and its graph-making! Hopefully you find it interesting too!

The inaugural culprit is this article in The Atlantic, which is maybe behind a paywall for you. That’s okay! I don’t really recommend it, and would instead direct you to this better article by Oregon Public Broadcasting. As a tldr; voters passed Oregon Measure 110 fairly overwhelmingly, which decriminalized drug possession and implemented funding for a broad range of outreach and treatment options that were intended to replace drug convictions.

The basic idea is that addiction is a medical issue and so treating that issue is probably a more effective approach than throwing people in jail. This is commonsense change if you genuinely think that addiction is a medical issue, because, uh, cops are obviously not medical professionals. The idea of throwing cancer patients in jail to treat cancer is ridiculous, and for people who genuinely think of addiction as a medical issue, the way we commonly treat addicts in the United States is similarly wrong-headed.

On the other hand, people commonly assume addiction is moral failure rather than a medical issue, and it is genuinely more challenging to do so. With something like strep throat, it is fairly straightforward to say “this is caused by a bacteria, we will prescribe antibiotics, the antibiotics will cure strep throat.” For addiction, the theoretical model that is currently in vogue is called the biopsychosocial model, and an explanation for addiction in that model would be something like “well this person had a genetic predisposition to addiction as well as a history of trauma and so statistically was much more likely to become an addict, so when they were prescribed opioids for a broken foot, there was a much higher chance that they would become addicted than other people who were prescribed the same medications in similar circumstances.” Obviously this lacks the tidiness of the strep throat example.

The legacy of viewing addiction as a moral failing also makes it particularly tricky when treating addiction doesn’t work. Obviously there are many medical conditions where treatment is not infallible (many people continue to die from cancer, for example), but because addiction has primarily been viewed as a moral failing for so long, it is quite common to hear people say things like “if they even want to be helped” about addicts, in response to a situation equivalent to cancer failing to go into remission. This is an understandable mistake to make, because in many cases there is little visible change to an addicts behavior. This is because addiction literally rewires how your brain works, and that rewiring is a major driver of behavior for addicts. In my own experience, there was a five year period of time during which I unsuccessfully tried to quit smoking. During that time I wanted to stop smoking but my actual behavior changed very little.

All of these factors conspire to make decriminalization efforts like Measure 110 contentious. And to be fair, by all accounts Measure 110’s implementation has not been without flaws. Per the OPB article, there are a couple main pain points:

- Although drug possession was decriminalized in early 2021, the actual support services for drug users ended up taking multiple years to staff up, and so perhaps a better strategy would have been to start funding those services prior to decriminalizing possession, so that addicts could still be referred to drug courts while alternate services were being built out.

- Under Measure 110, criminal charges were replaced by a $100 fine, which can be waived by calling an addiction hotline. This was intended to be the stick driving addicts towards treatment services, but by all accounts it has been quite ineffective.

So certainly Measure 110 is not immune to criticism, and at various points the Atlantic article does make some reasonable criticisms, many of which are echoed in the OPB article. The particular passage that got my dander up, however, is this:

The consequences of Measure 110’s shortcomings have fallen most heavily on Oregon’s drug users. In the two years after the law took effect, the number of annual overdoses in the state rose by 61 percent, compared with a 13 percent increase nationwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In neighboring Idaho and California, where drug possession remains subject to prosecution, the rate of increase was significantly lower than Oregon’s. (The spike in Washington State was similar to Oregon’s, but that comparison is more complicated because Washington’s drug policy has fluctuated since 2021.) Other states once notorious for drug deaths, including West Virginia, Indiana, and Arkansas, are now experiencing declines in overdose rates.

The Atlantic

While the statistics cited here are factually correct, this is not a good analysis. We’ll look at why in detail soon, but just so you have the information the two datasets that I used for this analysis are:

- National Center for Health Statistics. VSRR Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. Date accessed 2022-07-21. Available from https://data.cdc.gov/d/xkb8-kh2a. This dataset is linked at a couple points in Atlantic article.

- The csv export from this page of the CDC’s website, also accessed on 2022-07-21

So let’s start with some data from source #2, which I slightly prefer because it is not provisional data, and because it has overdose mortality per 100,000 people, which lets us more easily compare populations of different sizes. The downside of this dataset is that because it is not provisional data, it stops at 2021.

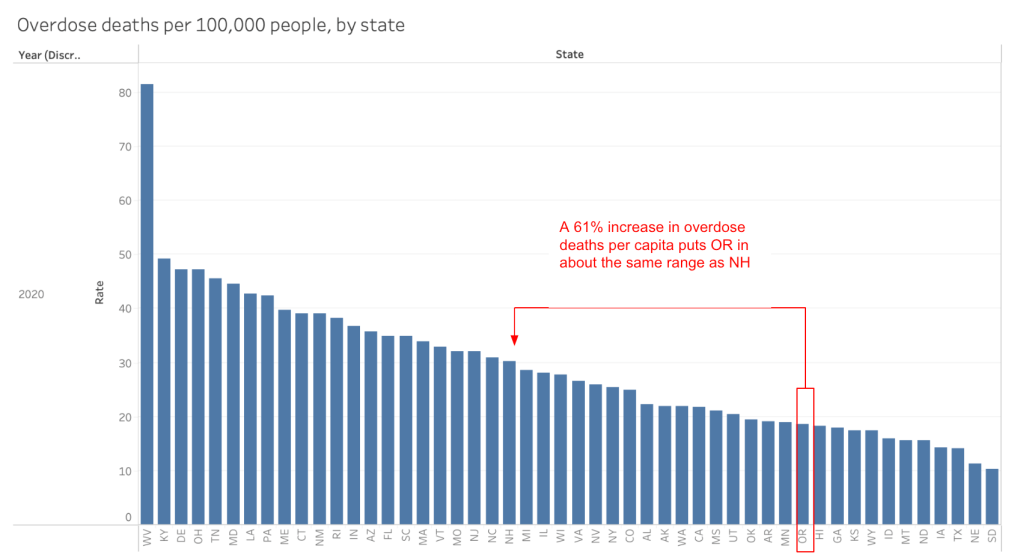

As a baseline, let’s look at how Oregon’s overdose death rate per capita compares to other states:

Comparing the final overdose data to the provisional data is a little bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison. As a couple of technical notes:

- The Atlantic’s 61% increase number is comparing overdose counts in Jan 2021 to counts in early 2023.

- This graph is showing numbers from the end of 2020, which is close, but not identical to Jan 2021

- I also did a quick check comparing the provisional numbers against this same graph for 2021 and 30-31 deaths per 100,000 people seems like it is the correct range calculated in a couple of different ways, which lines up with New Hampshire or North Carolina as comparison states.

So one important piece of context we can pull from this graph is that the 61% increase cited by the Atlantic takes Oregon from on the low end of states for overdose deaths to middle of the pack (assuming no other states saw increases. in overdose deaths, which is unlikely. There is a lot of overheated rhetoric about Portland in particular as a den of lawlessness in conservative media, and I do think that it is important to observe that at worst, even if decriminalization was definitely responsible for all of that increase, it has resulted in only an average amount of lawlessness (in at least this one dimension).

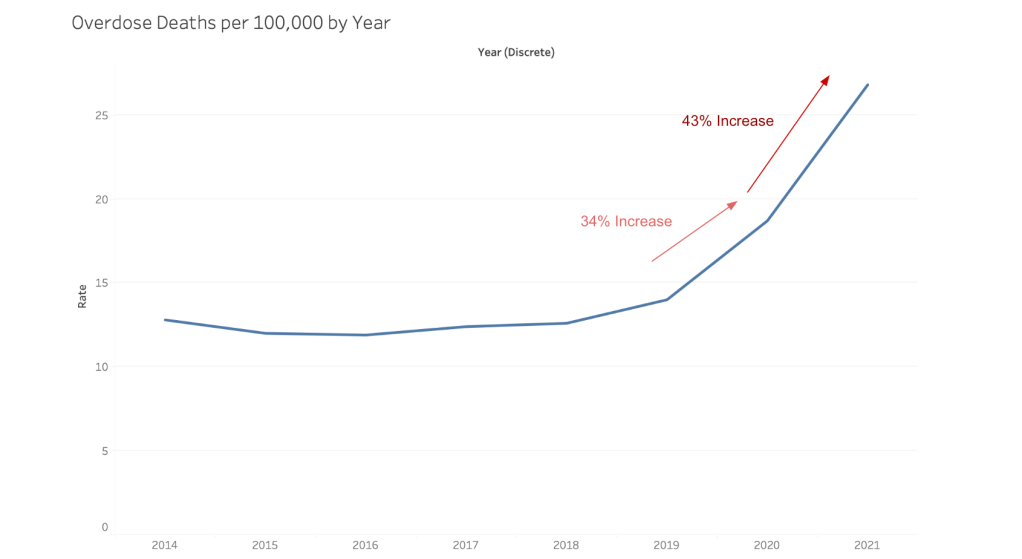

But of course there are reasons to suspect that Measure 110 is not entirely responsible for the increase in overdose deaths. The primary reason to suspect that is the ding dang increase in overdose deaths started a full year before decriminalization took effect:

Remember, for this dataset, we are talking about end of year numbers. Decriminalization took effect in Feb 2021, so the 2021 overdose count captures almost the first full year of decriminalization. Because the increase in overdoses preceded decriminalization, probably the worst thing we could attribute to Measure 110 is accelerating a preexisting trend.

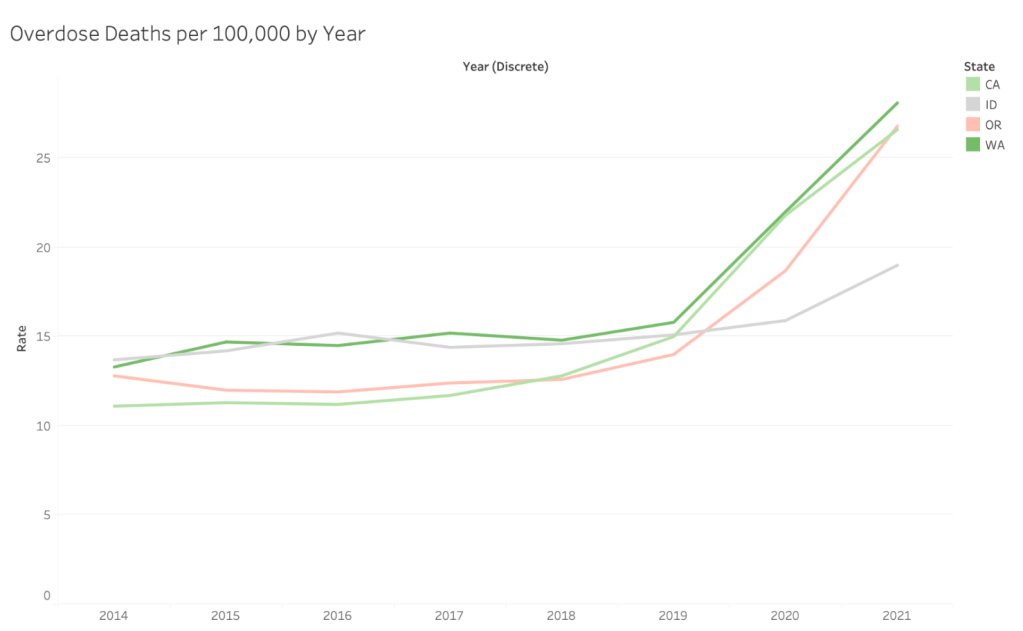

And if we compare Oregon’s trajectory to the comparison states cited in the Atlantic article, it seems like a common trend!

Here Idaho is a clear outlier, but for Oregon, Washington, and California we see the same basic trend. Oregon’s increase is a bit higher over this time period than Washington and California, but not dramatically so. Because the increase in overdose deaths predate decriminalization, and because we see a similar pattern among several states, a better comparison would be something along the lines of “from 2019-2021, overdose deaths increased by 91% in Oregon but only 77% in Washington and California.” At most, the increase in overdose deaths that we could attribute to decriminalization is that 14 percentage point difference (although a better explanation for that difference would just be that California and Washington already had higher overdose rates than Oregon).

The Atlantic also is doing a lot of work with its choice in comparison states. It, for example, dismisses Washington’s similarity to Oregon because “Washington’s drug policy has fluctuated since 2021.” The changes seem to have been that possession switched from a felony to a misdemeanor. It also includes Idaho but does not consider Alaska, for example.

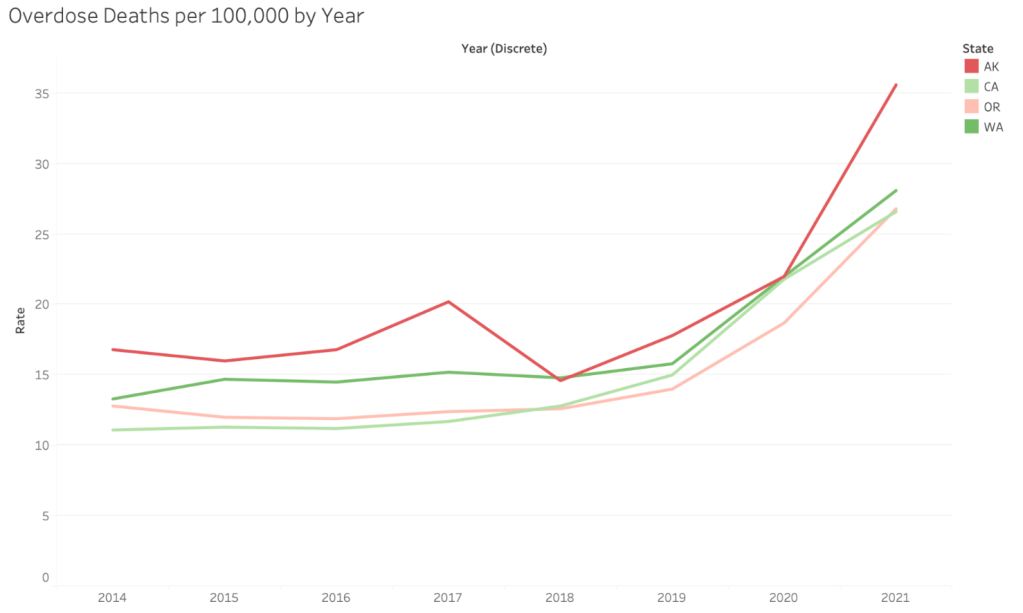

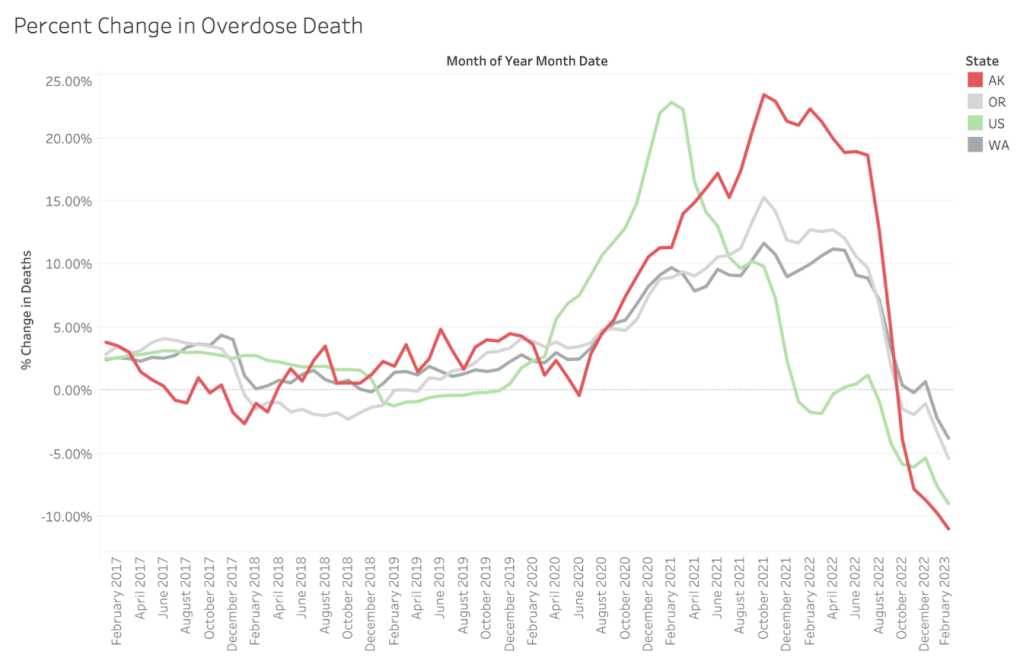

But if we remove Idaho and add Alaska to the dataset, this is what we see.

Notably, Alaska saw a 62% increase in overdose deaths in a single year, without any change in drug policy. The key takeaway here is that even independent of drug decriminalization, literally every state touching the Pacific Ocean saw sharp increases in overdose death per 100,000 people. Because we are seeing similar patterns in many states with different drug policies, this means that something else is going on! Two blindingly, blindingly obvious explantions are:

- The global coronavirus pandemic, which, uh, there was a lot of reporting at the time about how it was leading to increased substance abuse, and which pretty obviously correlates to the increase in overdose deaths.

- Another obvious culprit would be the introduction of fentanyl. OPB notes “fentanyl seizures in Oregon and Idaho increased from 27 doses in 2018 to 32 million in 2022, a 118 million percent increase.” As we shall see, Idaho’s overdose rate was less immune to this increase than it has seemed so far.

Of course, the Atlantic was relying on the monthly provisional data, so perhaps it paints a different picture? There are a few things to note about this data set:

- These overdose counts are for a full year that ends in the listed month (e.g. Jan 2021 includes all overdoses between Feb 2020 and Jan 2021).

- The data export itself just lists total number of deaths, this makes it a bit trickier to compare populations of different sizes, but most importantly, because population changes aren’t taken into account, the numbers are going to be slightly misleading. For example, if a state saw a 10% increase in population and also a 10% increase in overdose deaths, per capita the overdose death rate would remain the same, but in this dataset the death rate would appear to have increased.

- So that we can compare death rates in states with differently sized populations, we will be looking at the percent change from previous year (e.g. July 2023 would be compared to July 2022).

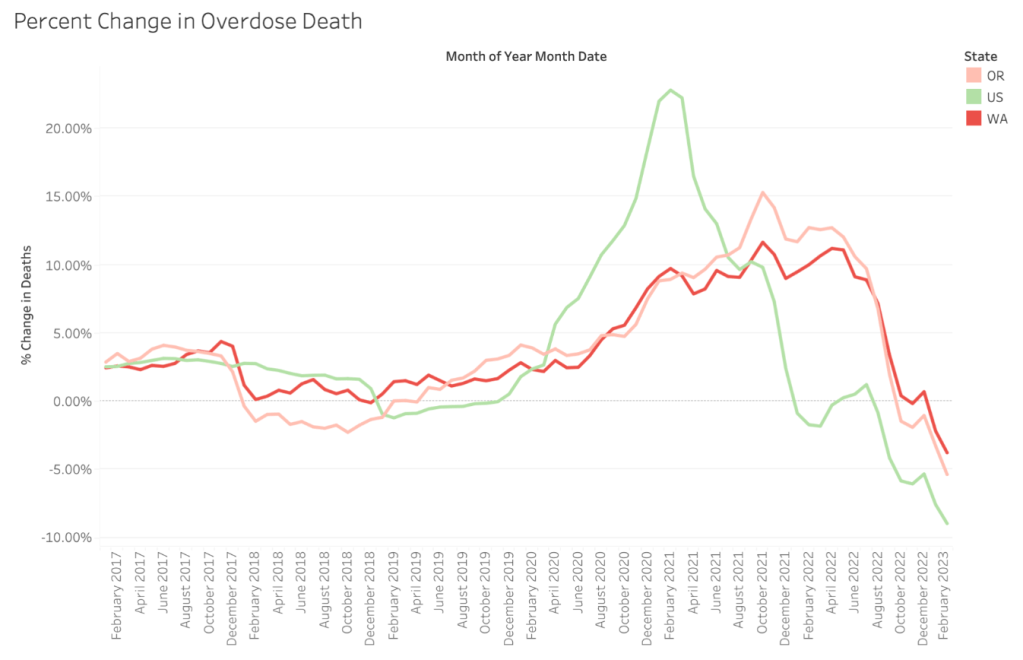

Let’s start by looking at how Oregon and Washington compare to the US overall.

For the US overall, we see a rapid increase in overdoses that starts with the pandemic, peaks in early 2021, and has started to decrease by early 2022. For Oregon and Washington, overdose rates increase more slowly during the pandemic and peak in mid-2022. Overdose rates have started to decrease, but not until late 2022 and early 2023. This means that when the Atlantic says that Oregon’s overdose deaths have increased faster than the country as a whole, the missing context is that prior to the period in consideration, overdoses increased much faster for the US as a whole than they ever did Oregon.

If we add California into the mix, we can see that it more closely resembles the US than Oregon or Washington.

Alaska, on the other hand, looks like a very exaggerated version of Oregon and Washington:

Idaho’s change in deaths is perhaps the most interesting of all the comparison states:

Idaho actually saw consistently high increases in overdose deaths from Aug 2020-Aug 2022, before those deaths dropped off somewhat more sharply than Oregon or Washington. That means that when the Atlantic notes that Oregon’s overdose deaths increased more than Idaho’s since decriminalization, part of the picture is just that in Idaho, the increase in overdoses had already happened prior to decriminalization. If we look at a longer timescale, the increase in overdose deaths is actually fairly similar. From Jan 2019 through Jan 2023, Idaho’s overdose deaths increased by about 20% whereas Oregon’s increased by about 23%, for example. Is that 3 percentage point difference decriminalization’s fault? Maybe!

The per capita dataset hides this increase because Idaho’s population grew much faster than Oregon’s (5.4% from 2020-2022 compare to Oregon’s 0.1%, per the dataset accessed here). One explanation might be that a fairly large share of the folks moving to Idaho are from demographic groups less likely to overdoes (e.g. richer, more educated), which is why the population increase has hidden an otherwise similar pattern of overdose deaths, but that is just a guess. It might also just be the case that more population = more overdose deaths, but I think the fact that overdoses are increasing faster than population growth, the fact that Idaho’s pattern of overdose deaths is similar to neighboring states (somewhat so in the case Oregon. and Washington, very much so in the case of Montana and Wyoming), and the fact that the increase corresponds to a known increase in fentanyl all make me suspect that what we are seeing is just new arrival being less likely to overdose than incumbents and hiding a similar problem.

What conclusions should we draw?

- We should be skeptical when journalists employ statistics, because they are not necessarily very good at it.

- Oregon’s drug problem is sort of middle of the pack among states, and the states that do have the most severe drug problems are rarely called “open air drug markets” by national media outlets. It’s important to think about why that is!

- At least part of the picture is a concerted effort by conservative ideologues to attack liberal places and policies (which is why the lawlessness of Portland and San Francisco is consistently highlighted even though they are not top locations for overdoses, violent crime etc).

- Another part of the picture is that places like Ohio and West Virginia have less expensive housing, and so people are doing drugs in their houses instead of visibly, as homeless people.

- Measure 110 seems unlikely to be the main driver of overdose rates, because:

- Overdose rates and numbers started rising prior to decriminalization, which seems to be related to the pandemic.

- Overdose rates or numbers rose in many nearby states at the same time, and also declined at the same time, which suggests that something else is the explanation.

- At the same time, it would be quite difficult to say that Measure 110 is having the intended impact, essentially because overdose deaths in Oregon are basically doing the same thing as neighboring states.

- All else being equal, it seems like it is probably preferable to arrest fewer people if the outcome is basically just an average number of overdose deaths, if only to save cops time.

Leave a comment